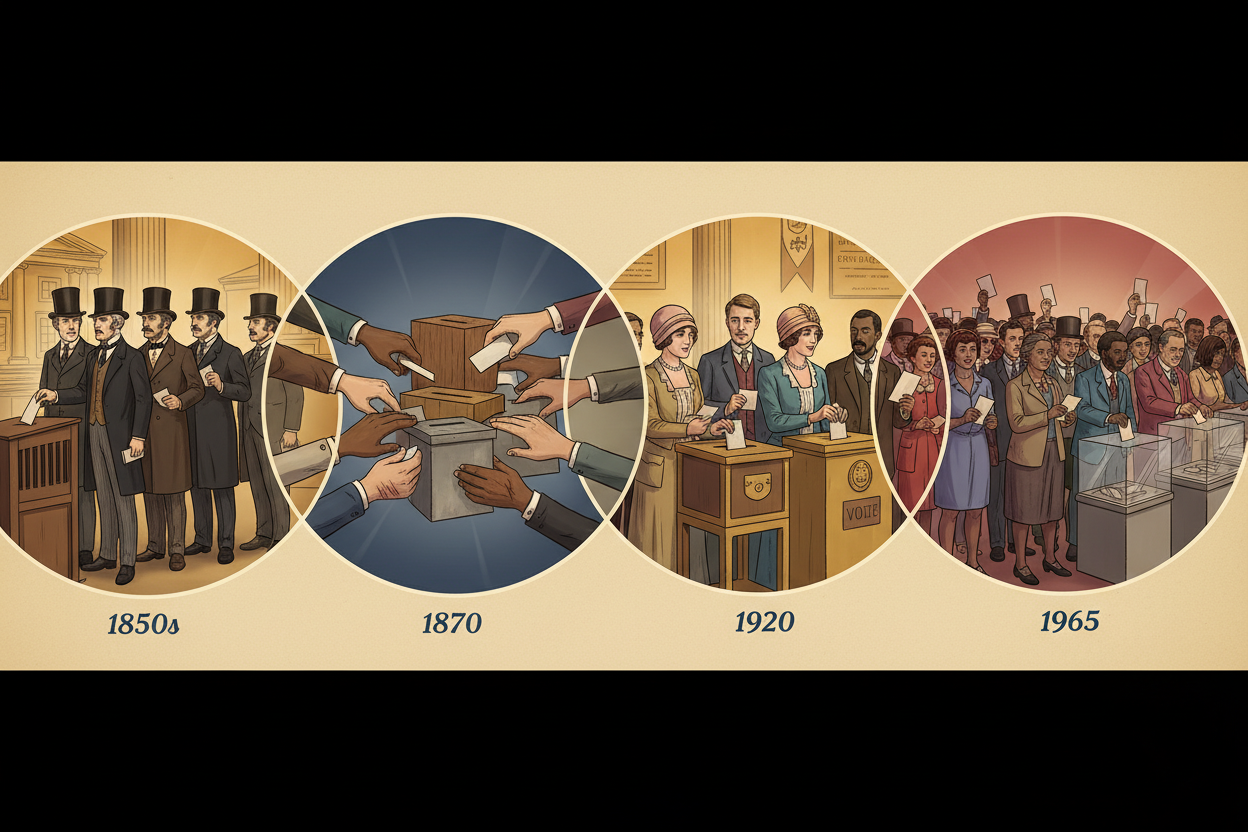

The Evolution of Voting Rights in America: A Historical Overview

The right to vote stands as one of the most fundamental pillars of American democracy, yet the path to universal suffrage has been anything but straightforward. From the nation’s founding, when voting was restricted to a small elite group, to today’s ongoing debates about voter access, America’s voting rights story is one of gradual expansion, fierce resistance, and hard-fought victories.

Understanding this evolution isn’t just about memorizing dates and amendments—it’s about grasping how our democracy has slowly but steadily become more inclusive. Each generation has faced the question of who deserves a voice in government, and the answers have shaped the very fabric of American society.

The Founding Era: Democracy for the Few

When the Constitution was ratified in 1788, the founders left voting qualifications largely to individual states. This decision reflected both practical considerations and deep-seated beliefs about who was capable of participating in democratic governance. The result was a patchwork of restrictions that limited voting to white male property owners—roughly 6% of the adult population.

These early voting restrictions weren’t seen as contradictory to democratic ideals by most contemporaries. Property ownership was viewed as evidence of a person’s stake in society and their independence from undue influence. The thinking went that only those with economic independence could make truly free political choices.

Different states implemented varying requirements. Some demanded ownership of land worth a certain amount, while others required payment of taxes or possession of other forms of property. These barriers effectively excluded not just women, enslaved people, and free Black Americans, but also many white men who worked as laborers, servants, or in other occupations that didn’t provide property ownership opportunities.

Early Expansions: The Rise of Universal White Male Suffrage

The first major wave of voting rights expansion began in the early 1800s and continued through the 1850s. This period saw the gradual elimination of property requirements for white men, driven by several converging forces that reshaped American political culture.

The War of 1812 played a crucial role in this transformation. Many men who couldn’t vote had fought bravely for their country, making property-based restrictions seem increasingly unjust. Political parties, particularly the emerging Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson, recognized that expanding the electorate could provide them with new sources of support.

Western territories and new states led much of this change. Places like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio entered the Union with constitutions that imposed few or no property requirements for voting. This created pressure on older states to liberalize their own voting laws to remain competitive and avoid losing population to more democratic neighbors.

By 1856, property requirements for voting had been eliminated in all but a few states. This expansion was dramatic—the percentage of adult white males eligible to vote jumped from about 70% in 1800 to over 90% by mid-century. However, this democratization remained strictly limited by race and gender.

The Civil War Era and the 15th Amendment

The Civil War and its aftermath brought the first constitutional guarantee of voting rights. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, declared that the right to vote could not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This represented a revolutionary expansion of democratic participation, at least on paper.

During Reconstruction, Black men exercised their newfound political rights with remarkable enthusiasm and effectiveness. In states across the South, Black voters helped elect Black representatives to Congress, state legislatures, and local offices. For a brief, shining moment, American democracy became significantly more inclusive.

However, the promise of the 15th Amendment proved fragile. As federal troops withdrew from the South and Reconstruction ended, white supremacist groups launched a systematic campaign to disenfranchise Black voters through violence, intimidation, and increasingly sophisticated legal mechanisms.

The Jim Crow Era: Legal Disenfranchisement

The period from the 1890s through the 1950s witnessed the most systematic effort to restrict voting rights in American history. Southern states developed an arsenal of legal tools designed to circumvent the 15th Amendment while maintaining a veneer of constitutional compliance.

Poll taxes required voters to pay a fee before casting ballots, effectively excluding many poor Black and white citizens. Literacy tests demanded that voters demonstrate reading and writing skills, but were administered subjectively by white registrars who could pass illiterate whites while failing educated Black applicants. Grandfather clauses exempted men whose grandfathers had voted before 1867, which excluded virtually all Black men while protecting poor whites.

These restrictions were devastatingly effective. In Louisiana, for example, Black voter registration dropped from over 130,000 in 1896 to just 1,342 by 1904. Similar patterns played out across the South, creating an electoral system that excluded most Black citizens for more than half a century after the 15th Amendment’s ratification.

Women’s Suffrage: The Long Fight for the 19th Amendment

While the post-Civil War amendments focused on racial equality, women remained excluded from voting throughout the country. The women’s suffrage movement, which had been building since the 1840s, faced the enormous challenge of overcoming deeply entrenched beliefs about gender roles and women’s proper place in society.

The movement employed diverse strategies over several decades. Some suffragists focused on state-by-state campaigns, winning victories in western territories and states where women’s contributions to frontier life had earned greater respect. Others pursued a federal constitutional amendment, believing that only national action could overcome resistance in more conservative regions.

World War I provided a crucial catalyst for women’s suffrage. Women’s contributions to the war effort—working in factories, serving as nurses, supporting the troops—made arguments about their unfitness for political participation seem increasingly hollow. President Woodrow Wilson, initially opposed to women’s suffrage, eventually endorsed a constitutional amendment.

The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, prohibited denial of voting rights “on account of sex.” This doubled the eligible electorate overnight, though Black women in the South continued to face the same discriminatory barriers that excluded Black men.

The Civil Rights Movement and the Voting Rights Act

The modern civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s made voting rights a central focus, recognizing that political power was essential for achieving broader equality. Organizations like the NAACP, SCLC, and SNCC organized voter registration drives, challenged discriminatory practices in court, and staged dramatic protests that captured national attention.

The 24th Amendment, ratified in 1964, eliminated poll taxes in federal elections. However, the most significant breakthrough came with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, passed in the wake of the violent confrontation at Selma, Alabama, where peaceful protesters were brutally attacked while marching for voting rights.

The Voting Rights Act was revolutionary in its approach. Rather than simply prohibiting discrimination, it required federal approval for voting law changes in areas with histories of discrimination and authorized federal officials to register voters directly. The results were immediate and dramatic—Black voter registration in Mississippi jumped from 6.7% to 59.8% within two years.

Modern Developments and Ongoing Challenges

The expansion of voting rights continued in the following decades. The 26th Amendment, ratified in 1971, lowered the voting age to 18, largely in response to arguments that those old enough to fight in Vietnam were old enough to vote. Various federal laws have also expanded access for Americans with disabilities and those who speak languages other than English.

However, voting rights remain a contested issue in contemporary America. The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder struck down key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, leading to new debates about voter ID laws, early voting restrictions, and other policies that affect electoral access.

These modern debates often echo historical arguments about voting rights, with supporters of restrictions citing concerns about election integrity and opponents arguing that such measures disproportionately affect minority and low-income voters. The challenge remains balancing legitimate security concerns with the fundamental democratic principle of broad electoral participation.

Lessons from History: Progress and Persistent Challenges

America’s voting rights evolution reveals several important patterns. Progress has rarely been linear—periods of expansion have often been followed by retrenchment and new forms of exclusion. Change has typically required sustained political organizing, often spanning decades, combined with favorable political circumstances.

The story also demonstrates how legal victories can be undermined without continued vigilance and enforcement. The gap between the 15th Amendment’s promise and its delayed fulfillment illustrates how constitutional rights mean little without the political will to enforce them.

Perhaps most importantly, this history shows that voting rights have never been self-executing or permanent. Each generation has had to actively defend and extend democratic participation, often against significant resistance from those who benefit from exclusion.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Journey Toward Democratic Inclusion

The evolution of voting rights in America tells a story of gradual but persistent expansion of democratic participation. From the limited democracy of the founding era to today’s more inclusive system, the journey has been marked by both inspiring progress and disappointing setbacks.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate both how far we’ve come and how much work remains. The right to vote, once limited to a tiny elite, now extends to virtually all adult citizens. Yet debates continue about how to balance electoral access with security concerns, and new challenges emerge as technology and society evolve.

The voting rights story reminds us that democracy is not a destination but an ongoing project. Each generation must decide anew who deserves a voice in government and how to protect that fundamental right. As we face contemporary challenges to electoral participation, we can draw inspiration from those who came before us, fighting to expand the promise of American democracy to include all citizens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: When did all American citizens gain the right to vote?

A: There’s no single date when all Americans gained voting rights. The process was gradual: property requirements were eliminated by the 1850s for white men, the 15th Amendment (1870) prohibited racial discrimination, the 19th Amendment (1920) extended rights to women, and the Voting Rights Act (1965) provided enforcement mechanisms. However, some restrictions still exist, such as felony disenfranchisement laws in many states.

Q: What was the most significant expansion of voting rights in American history?

A: The 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was probably the largest single expansion, roughly doubling the eligible electorate. However, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was perhaps more significant in terms of making voting rights meaningful for millions of African Americans who had been effectively disenfranchised despite constitutional protections.

Q: How did the Voting Rights Act of 1965 differ from previous civil rights legislation?

A: Unlike earlier laws that simply prohibited discrimination, the Voting Rights Act included enforcement mechanisms such as federal oversight of elections in areas with histories of discrimination and the ability for federal officials to directly register voters. This proactive approach made it much more effective than previous legislation.

Q: Why were property requirements for voting originally considered democratic?

A: Founding-era Americans believed that property ownership demonstrated a person’s stake in society and independence from outside influence. They worried that those without property might be easily manipulated by employers or others, making them unreliable democratic participants. This view reflected 18th-century ideas about independence and citizenship that seem exclusionary today.

Q: Are there still restrictions on voting rights today?

A: Yes, several restrictions remain. Most states prohibit voting by people with felony convictions, though policies vary widely. Voters must register in advance in most states, and various ID requirements exist. There are also ongoing debates about early voting, mail-in ballots, and other aspects of electoral access that affect different groups differently.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.